I felt like Robinson Crusoe on the first day of school. My mother told me I was going to embark on various adventures on an empty island. It was a place which would make everything beautiful if I went there every day and, thanks to that place, people bought me colored pencils, bags, coloring books and notebooks. I was bored of the stories I memorized, I wanted to read other things. School was a place I never met until that day and I surely didn’t think of how I could survive. I was only worried and excited. I held the hands they told me to hold. I remember her name was Işıl. We had to follow the path of the ones before us. So, we walked into the classroom.

First Step to Class Discrimination

I started elementary school in Yalova. I continued my education with the same teacher for five years. Remembering those years was pleasant up to a point. I felt gratitude to my teacher because I was taught to be grateful. My elementary school teacher was sacred. She taught me syllables, stories, mathematics, life science, and practical information about daily life – these months have 30 days, my dear: April, June, September, and November – and it means the world to me. I was under the pressure of both Ataturk and being a hardworking Turk. I couldn’t remember what the students did to avoid being chosen to read aloud the Student Oath before the first school bell each morning or noon. During five years of elementary education, I went up to the rostrum for once and couldn’t read the Student Oath from my heart – I still vividly feel the hurriedness of that past anxiety. My teacher was not angry at me because I messed up nearly all the lines of the Student Oath.

Why wasn’t she angry at me?

From the first class to the fifth, the classrooms’ size varied from sixty to sixty-five students. Three people sat at each desk. School uniforms were blue and collars were – obligatory – white. Girls wore thick wool tights under skirts in wintertime. Legs were bare during summers. Boys wore pants which reflected their economic conditions below their belts. Pants’ legs were shortened, knees’ shape was formed, and boys wore corded velveteen pants in season and out of season… When these children entered the classroom in 1992 by holding each others’ hands, they were asked the occupation of their fathers first. Without caring about the occupation of their mothers, children respectively stood up and shyly told their names, surnames, occupation of their fathers, and how many siblings they had. The teacher either noted down or kept in mind the information of children, and separated them by their socioeconomic conditions in a short period of time; therefore, children learned being discriminated by class in classrooms.

I can see and understand all these things after many years – that’s why I write this, because I know for sure that everyone who reads or will read this had experienced similar things. The teacher, who separated 65 children to desks, did not only make class discrimination through socioeconomic criteria, but also played an important role in the creation of our personalities.

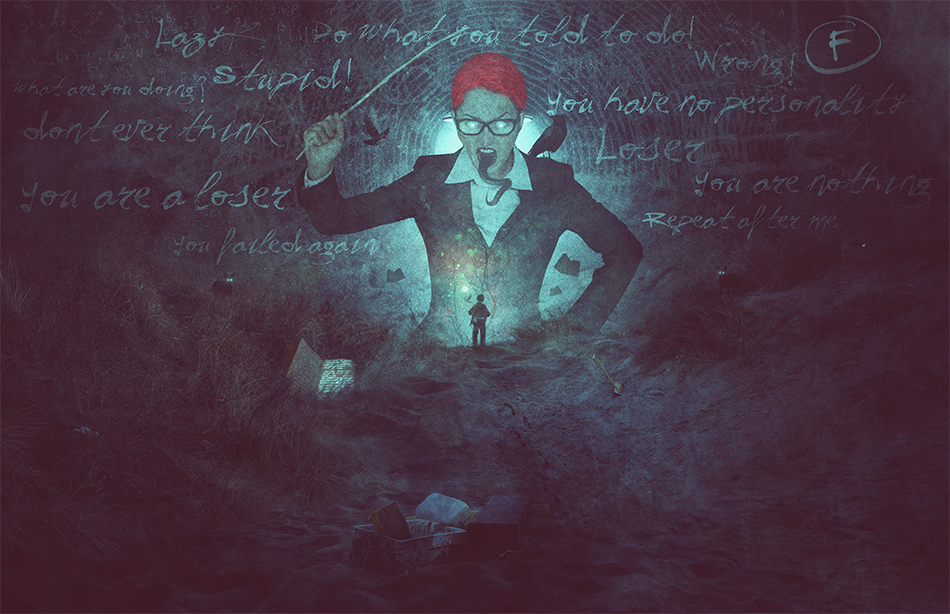

The Line of Whacking and Insult

Some students sat at front desks because their fathers either worked at governmental institutions, at the well-heeled fields of independent business or had a store at Fatih Street, or they were doctors, engineers, or teachers. Hard work and intelligence surely played a role in sitting at the front desk – but how much? The students whose fathers were below the average income distribution line among independent businesses were placed at middle desks. Doing homework and talent surely played a role in sitting at middle desks – but how much? Poor students, whose fathers didn’t gain a footing – according to the teacher – and didn’t earn well, sat at the back desks. Laziness and silliness surely played a role in putting each child, whose father wasn’t worth shit, at the back – did they?

I vividly remember everything. There was Osman with dark skin, thin hair, and almond eyes. I even remember his surname and student number. His father was a garbage man. He stood up and said, “My father is a garbage man.” Students near him congested their noses and grimaced as if Osman smelled like garbage. Then 64 children sided against Osman.

The board was green. Chalks were white, pink, blue. Osman often went near the board. Osman was often whacked. Osman was silly.

I wish I studied pedagogy, so then I could place this writing on a stronger discourse.

The front teeth of Osman were slightly separate. He was thrown at the back because his father collected our garbage, and he already internalized his place at the end of the first year. After being called silly once, could it be possible to expect sparkle in Osman’s eyes? It became easier to understand how the teacher encouraged the team of front desks to fight with Osman, for that team got carried away by the laziness of Osman when he couldn’t know the answers to the teacher’s questions. As Osman couldn’t know the answers and didn’t speak in case of not knowing, the teacher whacked Osman as a way of suppressing her anger – the teacher shouted don’t keep silent, for keeping silent was like a sin – and meanwhile, I saw his separate teeth between his small lips.

Osman was not the only one. Boys, whose names I can’t remember, near or in front of Osman, internalized mischievousness as fate and they underwent the same process. Their ears were pulled, cheeks were slapped, and they were belittled, humiliated. They were excluded from gym class – at the state school – because their sportswear was not appropriate. They were called to the board always and again, because they couldn’t put banknotes in the envelopes for helping the Turkish Red Crescent.

The line of whacking and insult crossed X-axis with the family of a child and Y-axis with the existence of the teacher from the first to fifth class of an ordinary state school in Yalova. I was never whacked and exposed to physical violence – thanks to my father? – and never belittled – was I intelligent enough? I always felt bad for not being whacked in elementary school. I always blamed myself for years because I couldn’t say anything to the ones who laughed and insulted Osman and others. I was a child who regularly did homework, tied her hair with colorful hair clips. I could never exist among the stars, I forgot my own troubles.

I remember each scene when the teacher called Osman and when Osman sheepishly walked towards the board by predicting he would be whacked.

My Beautiful Blonde Friend

I, too, was a child who lived in the imaginary world between the ages of seven and eleven, I only cared about dealing with my younger sibling – and I was supersensitive, as my grandma told. I was unaware of the need to object to the teacher – the system – for Osman. I was an ordinary child no one loved or liked. I was jealous of my blonde friends who were loved by everyone – was I jealous? Not sure. The feelings I remember are all about deficiency, something deficient in me, something I can cover with blondeness and beauty.

In elementary school, I experienced a turning point I could never conclude, justify, or overcome even if I continuously wrote about it. Now I want to simply write the story I fictionalized many times – writing it in a simple way will make things worse.

My friend S. was blonde. Her eyes were like blue beads. She was so beautiful. Her father’s economic condition was good, but S. was lazy. Even so, all the boys in the class, including the most handsome – and blond – boy C., were in love with her. No one was in love with me.

One day, we were studying the internal organs in life science class. To make us learn by seeing(!), the teacher brought the internal organs of a sheep from the butcher. Lungs first. White-pink. Completed with windpipe. The teacher wrapped the mouth of the windpipe with a napkin and blew in with all her power. Lungs swelled. We were astonished. Though we abhorred it, we were also fascinated by how the teacher blew the wet, veined pipe. Then liver. Bowels. Other organs. Bones. This and that bone. Thick and fatty bones. The teacher held the bones with a piece of paper and showed us.

Break time bell rang. I was sitting at the front desk – of course. The teacher collected all the organs and bones on the table and said to me, “Keep an eye on them during the break, we will continue in the next lesson.” With a sense of mission, I was protecting the stomach-turning organs and bones by hovering around the table, flies swarming over them. For a moment, S. came by and wanted to take a closer look at a thick bone – or something else happened, this part is blurry. Then the bone fell on the ground. It became dirty and dusty. It was covered in dirt. The bell rang, the teacher came in and looked at the bone on the ground.

She turned to me and asked something like what happened to this? I cannot remember whether I answered. Then she asked, holding the bone, “Who made this?” I cannot remember whether something else happened or she told something then. What I remember is that I pointed at S. sitting two or three desks behind me and told the teacher that she did it.

Teacher called S., I thought she was going to whack her.

She gave the bone, which had grey ends and was fatty and big, to S. I thought she was going to whack my friend with the bone – crossword puzzle, the end of a bone, epiphysis.

“Open your mouth,” she said.

- opened her mouth and the teacher put the bone in the small mouth of S. and pushed it up to her throat, until tears fell from her deep blue eyes.

Being jealous, envying someone, or desiring something I don’t own after seeing it at someone else was over for me. I lost my sensuality at that point.

My Dear Teacher

I vaguely remember my parents’ talks about my teacher. They said, “She is the best teacher in Yalova.” They were right. My elementary school teacher was a woman who intently chose her last two classes before retirement in the middle of 90s. She stood on slight heels for hours. She stood out amongst other teachers with her honey bubble curly hair. The exams for Anatolian High Schools and private schools were made after elementary school’s fifth grade back then. She made the highest number of students enter the Anatolian High School and private schools (Robert College) in Yalova. She was intensely proud of this – so were our parents and us. One day we visited her in her house – Why? I don’t remember. This day she told me about one of her students who was accepted in Galatasaray High School and told me I had enough talent to be accepted as well, I was fascinated – I could never do it. Instead of her, it was almost us who competed with Julide, the rivaling teacher.

Osman was not alone. In third class – if I’m not mistaken – Güher came from Erciş as a transfer student. He couldn’t speak proper Turkish and we couldn’t learn where Erciş was from. Extremely naughty, Berkay had an angry stance with his red cheeks. His father was one of the most dominant contractors in Yalova. Caner was beautiful but good for nothing. Yunus was a typical Black Sea boy with his big nose and he was good for nothing as well. Güher, Berkay, Caner, Yunus, and their friends were whacked for five years. They were whacked by the best teacher of Yalova, who placed students in Robert College or Galatasaray High School.

Like I turn back to my childhood to try to understand myself, I tried to understand my teacher A. as well. I tried to justify myself by thinking when I was seven, eight, nine, ten, and eleven, she was forty-seven, forty-eight, forty-nine, fifty, and fifty-one.

How much did I fear when pointing at S.? Was I afraid of being whacked though I sat at a front desk? I spent years thinking how I hurt S. I couldn’t let go of guilt, frustration, and wicked feelings. “But I was a child too” couldn’t be an excuse!

I still feel exhausted by being aware of how I can categorize the psychological and physical violence I (we) were exposed to directly or indirectly by the elementary school teacher. Though I’ve felt a little relieved after finding S. on social media and apologizing – and being forgiven by saying you were a child too – sometimes I’ve been losing sleep about not being able to stand up and say no although it was the right time to object something and not being able to tell about the things that happened in the classroom to my parents. Was it the behavioral responsibility of an adult, a teacher? I don’t know.

I base on my elementary school years in this writing. Only five years. Merely my childhood. I’ve told a little part of what I can tell. I don’t have an itch to tell more. My middle school and high school periods are at the core in other writing. I may write them one day as well. I want to write a conclusion for this; it’s so hard, but I can do it: everything I couldn’t oppose by saying no those years has shaped my present time. I witnessed the bullying of the person we called our teacher against whose authority we cowered. I couldn’t oppose bullying. My excuse was being a child and ignorant. I apologize first to myself, then to my classroom friends, but mostly to Osman and S. My dear elementary school teacher has been writing me on social media and telling me she has been proud of me for the last two years. I hope her opinion will not change after reading this.

Though you’ve taught us finding the 30-day months right away, we still cannot forgive you.

Translation: Gözde Zülal Solak

Illustration: Ahmed Emad Eldin

Be First to Comment